Ten Lessons From Loving London

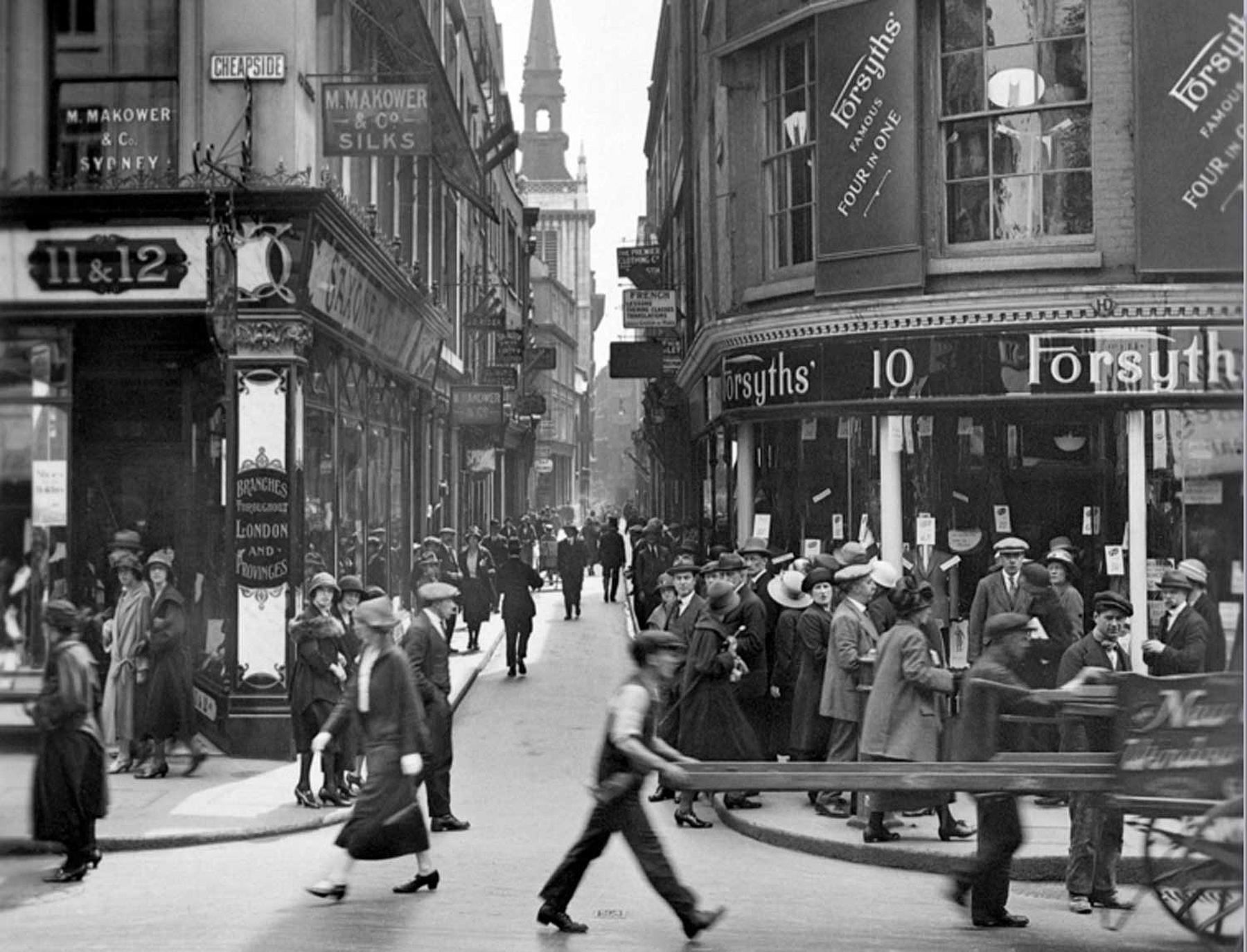

I was pleased, when I was asked to speak for 10 minutes at MIPIM on ‘a City I Love’, to find that no one else had chosen London; Tokyo, Algiers, Auckland, but not London. I am a Londoner through and through – my family was trading in silk from Cheapside in the mid nineteenth Century. Is that why I love London ? Or is it because it is loveable ?

I named my piece ‘Ten Lessons from Loving London’ and this is how it went:

One: London is like a patchwork, patched and re-patched; getting better with age. My relationship with it is that of an old friend; not too perfect; resilient, accommodating. Its character, to quote Venturi, is ‘hybrid rather than pure’.

Two: Napoleon said we were ‘a nation of shopkeepers’ and I agree. Market forces and the ‘un-designed’ realities of the market-place have dictated so much of London’s nature. The collage of the great family estates combined with the jigsaw puzzle of small freehold plots display, in Colin Rowe’s words (when comparing London with Rome) ‘the virtues of order with the value of chaos’.

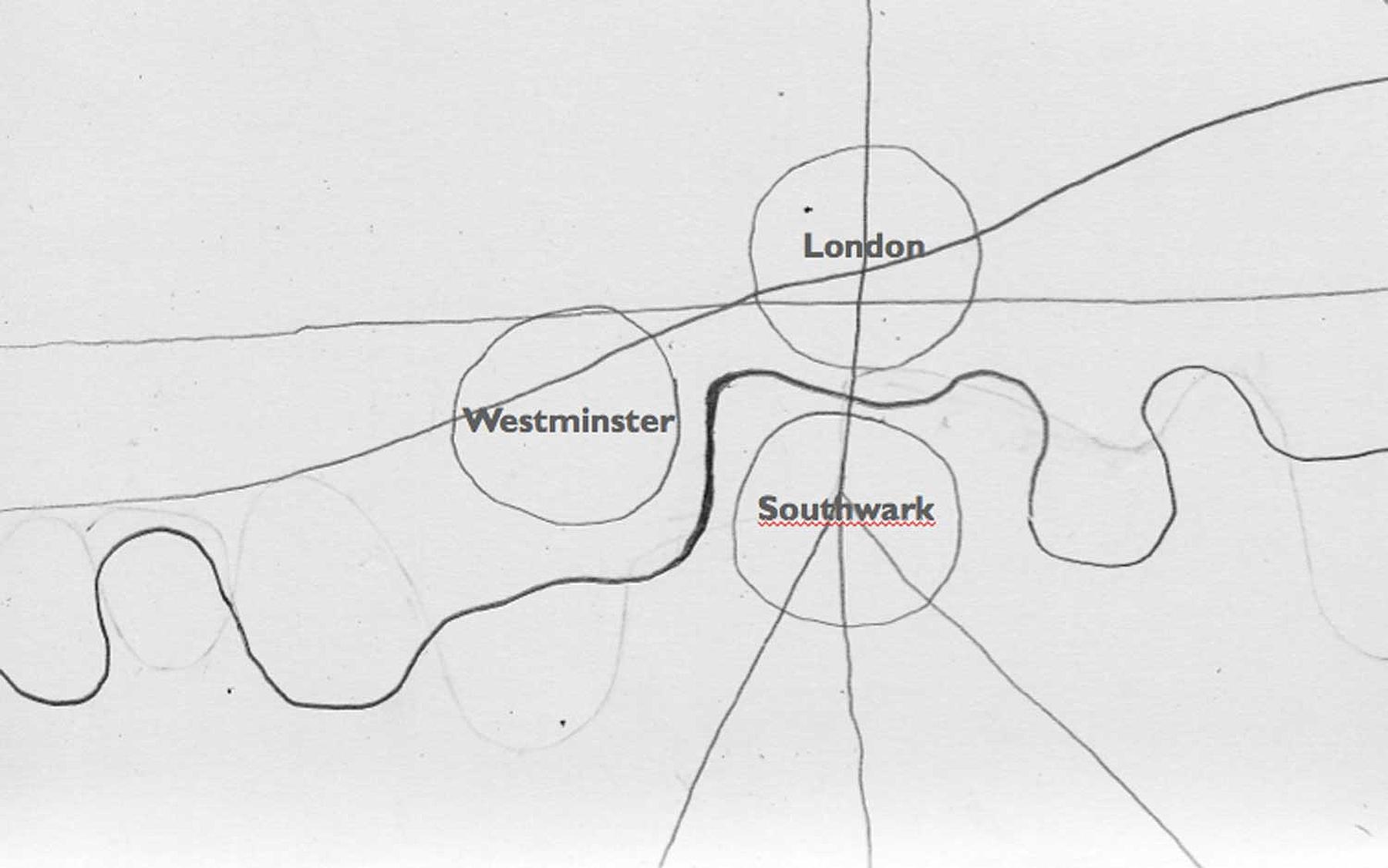

Three: London has balance – asymmetric and irregular – and, like debate at The Palace of Westminster, it thrives on differences; point and counter-point; East and West, North and South. It always surprises me how our main East West artery – the Thames – runs due North South at the centre; what I call the ‘Great Straight’; from Vauxhall to Waterloo Bridges. I grew up in the West but my own centre of gravity has gradually shifted Eastwards, just as it has for London as a whole, since I was a child.

Four: ‘Higgledy piggledy’ is one of my favourites words, and I think it sums up London well; it is an eccentric, comfortable pair of words with the straightforwardness to sound like what they mean. This is not just a matter of lines; responsive geometries, arising from constraints, giving us an ‘emerging view’ up Ludgate Hill to St Paul’s, rather than a straight vista along a grand avenue, in the French style, as Wren would have liked, or the curve of the Great Northern Hotel at King’s Cross which follows the ancient serpentine line of the River Fleet, flowing from the Vale of Health on Hampstead Heath, used as a drain and buried deep underground centuries ago, traced to the surface in lines of ownership to this day. It is also a matter of layers; the layers of history through which the story of the city is told.

Five: London is a conurbation of villages; its villages are its bone-structure. But, more than that, it is the ‘village in the city’ which accounts for so much of London’s life and identity; its pulse and its sense of self (collective and individual); its behaviour and its harmonics.

Six: London’s language is strong and clear whilst being spoken in many dialects, loud and soft; it is a living vernacular. Its vocabulary of terraces, mews, squares and communal gardens, porches, steps, bays and chimney stacks is legible and familiar; its grammar of fronts and backs, urban blocks and party walls is coherent. The punctuation marks and accents of endless ‘variations on a theme’ make everyday prose into a pleasing poetry

Seven: London’s trees are fine; I love the way they rise above the facades of buildings, making the street an interior. London is indeed a green city, with its great parks and many gardens, but somehow it is not too green; solid edges are its bone structure. Although part of its success is its green green suburbs, it is not a suburban city.

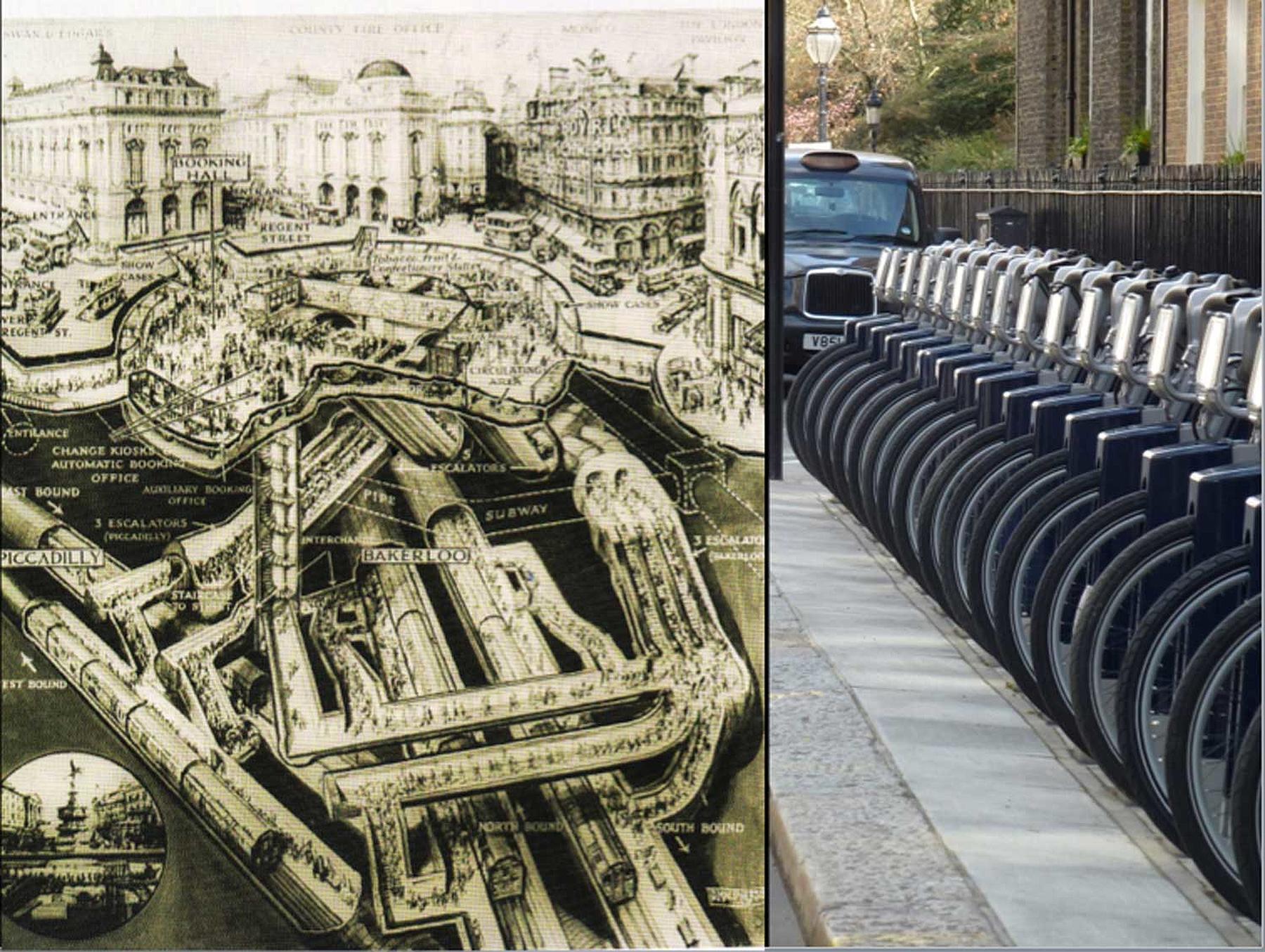

Eight: London’s transport is excellent and always getting better. I feel lucky, in what are known to be economic hard times, to be somewhere where so much is being invested in infrastructure and 2012 is only partly to be thanked for that. But I feel even luckier that I don’t have to use public transport. My faithful fifty thousand mile bike with my ‘office’ in front (my wicker basket) takes me everywhere. It always seems strange to me that as London grows, it shrinks; even by bike, Bromley by Bow used to be the edge of the world, now it isn’t far at all.

Nine: London is like a large flowerbed of arts and education; I love the fact that it blooms amongst the bricks and mortar and brings life and colour to the street. Market forces and cultural vision, old and young, intertwine and each nourishes the other.

Finally it is London’s robust adaptability which I love – it is an ever-changing organism, and has an ‘eco-system’ for survival. Is it ‘sustainable’ ? I don’t know, but I am sure it can be sustained. At the scale of the city and of the street, London is continually undergoing re-birth. The approach to re-use which we see along the banks of the River Lea is found all over London in its solid, ‘edge-making’ buildings, in a perpetual state of healthy flux; an inner world of flexible spaces; an outer world of public places.

When I had concluded my tribute to – or was it a manifesto – about London, I was asked what secret or surprising detail, in my experience of the city, touched me. Amongst the teeming crowd of fragments from London which have fascinated my imagination over the years, including the stories told by the blue plaques, the countless stories vanished into thin air and my own stories, told and untold, one jumped out. It was the shrapnel scars on the big stone walls of Tate Britain and the V&A. These surfaces have been rusticated twice; once by craftsman in the name of progress and posterity and a second time by bomb-blasts in the name of attack and defense; each time, hot metal shapes rock. Why am I moved ? Not so much as a memorial to the War, but rather as an example of how the three great dimensions of Space, Time and Memory can be compounded and made legible, as part of a living process.